Chicano Renaissance

How did you begin your journey as a photographer?

As far back as I can remember, I’ve always been drawn to documentation, specifically the camera. As a child, I loved being trusted with my family’s film cameras (digital at the time was a newer and more expensive technology; it was the 90s). Even when the film wasn’t loaded, I still loved to look through the viewfinder and pretend I had a photographic memory.

In 2003, I was in 8th grade and really struggling through my adolescence. At the time, I was living on Campo Indian Reservation, a rural First Nation community. There were a lot of struggles in my home life, and it affected much of my outside world. I was failing all my classes, dealing with poor mental health, and begging the universe for an outlet to escape the growing pains and poverty.

As a last-ditch effort to pass middle school, my mother pulled me from public schooling and enrolled me in a charter school in Pine Valley, California. It was there that I was introduced to photography as an actual class. Having the encouragement of my then teacher, Audra Hall, I really excelled in the subject. Photography truly took me away from my external struggles and gave me an outlet to emotionally regulate.

After 8th grade, I moved to the city of San Diego full-time and lived with my father. Things really turned around for me, and I found myself at the age of 15 on the campus of UCSD. By that time, I had put the camera down and picked up records and an appetite for music. I started volunteering at a collective called the Che Café and soon after started booking punk and hardcore shows. At the time I was still in high school, but it felt like a safe space to explore art, politics, and youth culture. That being said, the camera once again re-emerged. I was inspired by a lot of what I was experiencing and wanted to remember that era of my life.

Once I got into college, I wanted to understand the broader spectrum and art form of photography, so I enrolled in a series of classes with Patricio Chavez. I learned all the basics and then the more technical aspects like the darkroom and development. It was a very rewarding process and something that I felt came naturally.

After 2012, I put the camera down for a few years, and then in late 2014 I once again felt another shift in my life and needed to ground myself—the camera has always done that for me. By that point, I left the Che Café and no longer felt connected to the punk or hardcore scene that I had once felt at home with. So, naturally, there I was, 21 years of age, finding another path.

At the time I was working on my undergrad in journalism with an emphasis on Chicano studies, when I was introduced to Bucky Montero. She and a few colleagues had recently received a grant for the underserved community of Logan Heights, a place my family has called home for generations. At the time I was staying in Grant Hill, and it made sense for me to participate in the project they were funding through the grant—it was a community-powered radio station. Being in the barrio, not to visit family but in a social and artistic setting, was a completely different vibe and I knew it was a special time for Logan Heights. Some referred to that era as an emerging Chicano renaissance; the streets were being reactivated in ways that were positive and community-driven. I understood that I was in the depth of something special and that it wouldn’t always stay like this, so I started documenting once again—this time not for myself or “to remember,” but with the belief that one day these photos would tell a future generation about what this era was like. From the cars, community, style of dress and music, to the individual faces I captured. My inspiration really came from my father and his side of the family, who left behind amazing archives spanning from the 1920s–90s, and from photographers like John Valadez and Gusmano Cesaretti, whose work let my generation know what Chicano youth culture was doing in the 70s and 80s.

I now am at an age where I see my photography as an act of commitment and preservation to my community and family. There will be nothing more rewarding than a great-niece or grandchild appreciating a time I’ve preserved. I want nothing more than for viewers to know I am capturing celebrations of identity, belonging, and our shared history.

How have you grown over the years?

Over the last decade I’ve shifted the focus of my work in a few different ways. I have found my flow and confidence in what I do, I believe photography should always platform a greater purpose or tell a larger story, within the growth of my work I’ve found myself to be more intentional with what I share. I try to always focus on uplifting and inspiring rather than documenting negativity or somebody’s bad day. We are in a strange era right now with social media and the accessibility to it, that literally anyone can upload or share imagery and breaking news; although it’s a huge advancement for our communities, I feel that there is a level of responsibility and etiquette that comes with the art form of photography and sharing on platforms. I always side on the form of permission, which to some photographers might defeat the purpose especially when it comes to street photography, but I love having a mutual respect, communication and understanding with my subject matter.

When I first began photographing, I didn’t understand fully the power of a camera; the camera is key, and it can open doors to so many different worlds and people. But, in the same token it can also close people off, I understand that sometimes the opportunity may not exist to have the conversation before clicking the shutter but respect and announcing your purpose as a photographer goes a long way, over the years I’ve met some very special people who I otherwise would have skipped over had it not been for communicating and asking permission to photograph an aspect of their lives. Overall, I’ve grown to be more intentional with what I capture and respectful with what I share, whereas in the early years I was less cautionary and naïve, dare I say.

How would you describe your style?

That is a great question and something I am still formulating. Overall, I would say my style is documentary based with a strong emphasis of cultural storytelling.

Your work mainly focuses on lowrider and Chicano culture. Why do you connect with this subject matter? Why is it important?

My connection to this subject matter is rooted in my ancestral lineage, I am of Mexican ancestry and indigenous lineage on both sides of the Mexico and United States border. I am a dual citizen of Mexico and in the United States can trace my lineage back to roll numbers the United States government gave my family when they were escorted to Reservations in the 1800s.

My father and his five siblings relocated from Mexico to the United States, San Diego to be specific, in the 1960s when he was just 3 years old. Although he was a Mexican national, growing up in Southern California in the 60s and 70s he was heavily influenced and involved with the Chicano youth movement.

Growing up around Chicano/Mexican American culture in Southern California wasn’t an anomaly, it’s to be expected when that’s what your parents or guardians promote. I was very fortunate to have a father who survived gang culture of the 70s but encouraged pride in our people, the arts, and education. I document Lowrider and Chicano culture because it’s where I feel most at home, welcomed, and spiritually connected to. I am a firm believer that if we don’t document our own stories and culture someone else will do it for us, and as history tells, it’s not always flattering or factual.

How do you approach planned photoshoots versus documenting events, such as lowrider shows? Do you prefer one or the other?

When I first started diversifying my skills and began doing planned photoshoots, I would have told you that I prefer documenting events, because that came easy to me and was always very exciting. But now that I’ve managed to gain experience in both, I can honestly say I equally enjoy what both methods have to offer.

When documenting events, I love the spontaneity and unexpected. There is something very liberating about not being in control of the environment and just flowing with the energy of the space or subject matter, there is an indefeatable authenticity that can often be seen upon film development. Whereas planned shoots are in a more controlled environment, however, it does create a pressure to perform and have a finished product that the client will enjoy. There is an element of organized chaos and ultimate reward that comes with the completion of the photoshoots I’ve done for clients. I also really enjoy the endless education and self-improvement it takes, it’s a very healthy and character-building experience.

You are based in San Diego, California. What’s it like being an artist in San Diego? How does the city inspire you?

I am born and raised in San Diego, it’s a very diverse community and county that ranges from the ocean all the way to the mountains east of us. San Diego is more than just a city: it’s occupied Kumeyaay land. Many tribes and relatives were pushed from the coast to the mountains during the settlements and occupation of Spain, Mexico and the United States. Much of present-day San Diego city is built on old settlements and village sites, which I must acknowledge first and foremost.

From the 90s until now the cityscape has changed a lot; currently we are dealing with a huge housing crisis and neighborhoods re-developing overnight. A lot of people from the city are being pushed out as new development, investment and tech companies begin to enter the chat. We also share the busiest border entry known to the world, the San Ysidro border crossing. Being a border city, a military town, a first impression of the United States to many, we as fellow creatives and artists have a lot to digest, to be inspired by and to communicate to the world. I’ve always found my city and fellow creatives to be ambitious, independent, and openhearted.

Being in the “shadow” of Los Angeles (no shade), there is a sense of camaraderie that often surprises outsiders and in fact we pride ourselves on our “small town” energy. There is a lot of opportunity for artists in San Diego that are in all different points of their career. I find that just going outside and talking to people will connect you to some opportunity or another.

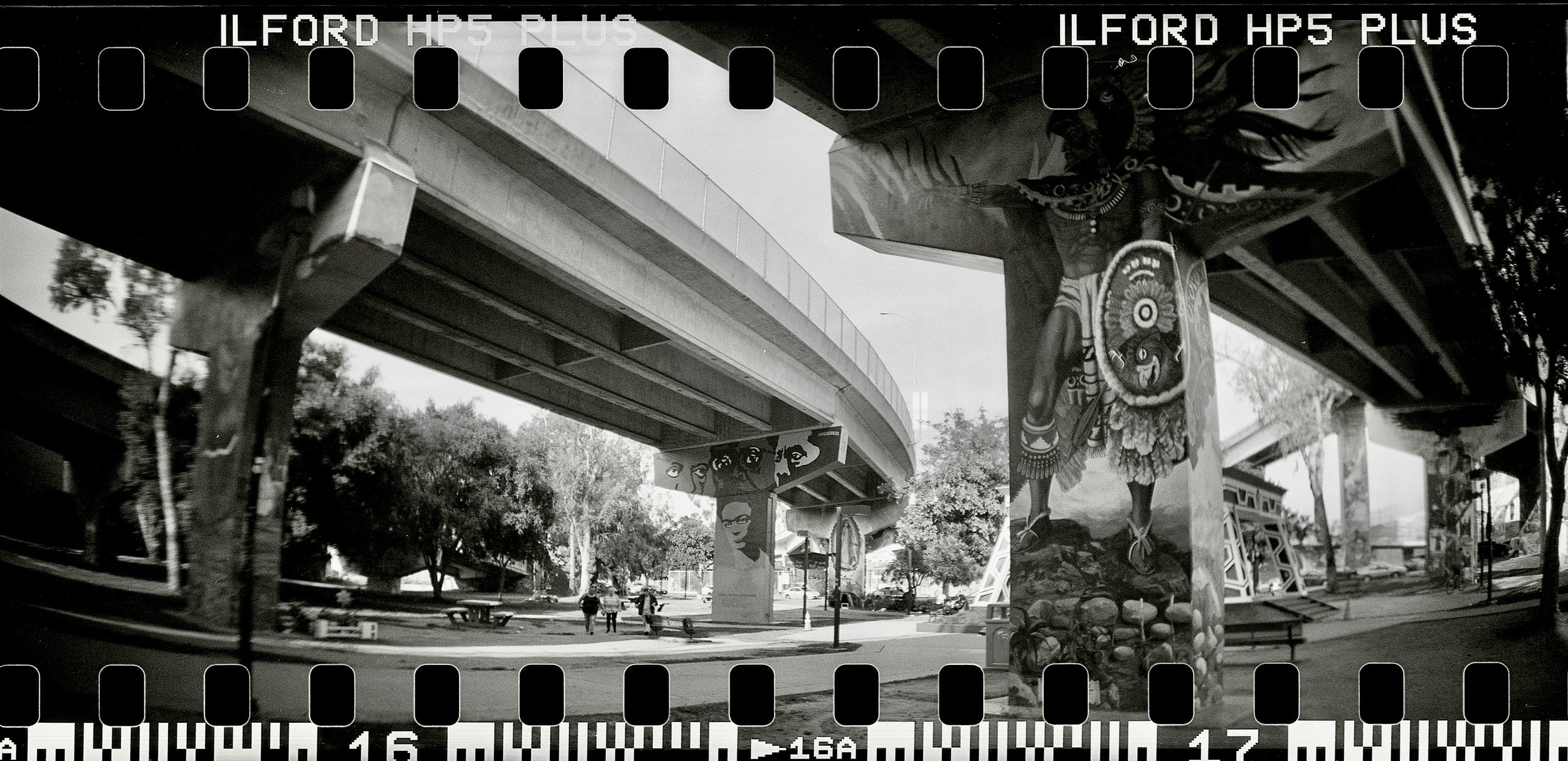

Artistically, I’ve always been inspired by the neighborhood my family comes from, specifically Logan Heights, Chicano Park. In the 1900s my great x2 grandparents settled on Irving Street; it was in that house my great grandmother birthed my maternal grandmother, aunts and uncles. My grandmother’s generation, specifically my Aunt Gloria Rebolledo, would later grow up to become one of the longest-standing members of the Chicano Park Arts Council. Through her work she contributed to the creation and preservation of murals in the park after the takeover. She also created the cactus garden and dug out by hand the kiva where they still hold ceremony some 40-plus years later. Chicano Park to me represents a pillar of culture, revolution, and community perseverance. Because of the work my Aunt Gloria, uncles and other relatives have done throughout the years, I always grew up holding a lot of respect for that piece of land and family history.

In 2020 I gained the opportunity to work on the Anastasio Hernandez Rojas Mural, a mural dedicated to Anastasio who died in the custody of U.S. Border Patrol agents. I had the honor of applying the clear coat which would preserve the mural for generations to come. Again, in 2021 I was invited back but this time to prep the pillar for the Brown Image Mural, and lastly in 2023 I had the final privilege of painting on the MEChA mural under lead artist José Olague. Contributing to the park and my family’s legacy of artistry in San Diego has been one of my greatest joys, although I must say all murals were completed with various groups of dedicated and talented artists. It was an immense privilege to work alongside everyone. Being a multigenerational artist in San Diego, especially one that leads back to the movement, is a huge honor and although I haven’t found my full form, I understand that it also carries a lot of responsibility, because when you are outside and in community you are representing your elders and lineage.

Tell the story behind one of your photographs.

This photograph, taken in 2018 with an Olympus Stylus Epic Zoom 80, documents a vibrant moment in San Diego’s recent history. Between 2018 and 2022, La Vuelta; a committee of Logan Heights community members, organized seasonal neighborhood car cruises and an end-of-summer festival. While rooted in the celebration of lowrider culture, La Vuelta’s greater mission was to uplift local businesses, many of which struggled with limited foot traffic and misrepresentations of the neighborhood. For a time, it was an undeniable success, drawing diverse crowds, sustaining shops and restaurants, and creating opportunities for emerging creatives such as photographers and DJs.

This day in particular captures young DJ Jeslow, then only nine years old, set up to play records for the block. His presence reflects the intergenerational spirit of La Vuelta, an event built for the community, by the community. To me, this photograph embodies the energy of that era, the opportunities it created, and the culture it nurtured. It also serves as a timestamp of the neighborhood before rapid development transformed the landscape, ultimately limiting the ability for events like La Vuelta to thrive in the same way.

For my own journey, La Vuelta was pivotal. It gave me space to sharpen my craft in street photography, to grow as an artist, and to bear witness to a moment when community, creativity, and culture converged on the streets of Logan Heights.

La Vuelta, 2018. DJ Jeslow.

In addition to documenting Chicano culture, you are a partner and creative director for the cannabis company, Sunnyside Lifestyle. What is the story behind this venture?

Sunnyside came into existence in 2022 as a path to legitimize our family business. I never imagined that I would work in this industry, but in doing so, I found it very important to question the longstanding narrative of cannabis, which often is portrayed negatively. I told myself that if this was the path I was going to take, I needed to be open minded, teachable, and sharpen my craft of commercial storytelling, and in time I have.

In the beginning, marketing, photographing and creating Sunny was very uncomfortable. I didn’t have a sense of direction or mentor in the industry from a photographer standpoint. My partners and I had to create the blueprint for how we wanted to proceed forward in our growth as a company. Sometimes it was difficult because we’re more of a “traditional” brand and that comes with its own set of cautionary tales. But being traditional also meant not all the same rules applied to us as it does with the white market. Within that I found myself having more freedom in creativity, but also equal risk.

Throughout the last couple of years, Sunnyside has successfully grown into a household name and recognizable brand in San Diego, Tijuana, and beyond. We have managed to do so through the determination of our sales team, guerrilla street style campaigning (large-scale wheat pasting, murals, and stickering) and ultimately our creative ability to market via photography, hand-to-hand transactions and social media. Being positioned as a creative director for this brand has really given me so much insight and strength when it comes to working within this industry and beyond. Translating my skill set from documenting my culture to cannabis has allowed me to question and shape a new generation of the emerging market that cannabis is experiencing. It’s a very exciting yet crucial time as we are creating the new standards and breaking the old rules. Ultimately, we are rooted in self-expression, community and the arts.

As a creative director for Sunny I am constantly challenging the norms of an industry now regulated by the same system and individuals who still try to criminalize and overtax our existence. For now I can say we have successfully done so and have had a lot of fun re-creating a different view and showcasing how cannabis is just another thread in the fabric of community and creativity. There is so much more to be said about that experience but for the sake of legality, all I can do is thank my team and especially my assistant of photography on sets, Amanda Pimentel.

How does your personal photography work influence your vision as a creative director?

My personal photography influences my vision as a creative director in many ways from the equipment and film stock I use; I consistently work with an Olympus Infinity Zoom 230 point-and-shoot and a Contax G2 film camera; both give a very distinguished finish that is hard to replicate. Furthermore, the people that I’ve made connections with through my personal work, I tend to funnel over to the professional side which is really awesome because I am able to compensate models for their time; it’s like from a car show shooting for fun to hitting them up and offering them a quick job. It’s my favorite thing pulling people from those environments and merging them into other opportunities.

I often think of my younger self when I was freelance modeling, I love being able to give people a good experience shooting with me and setting a standard for them as well, in regard to being compensated for their time and understanding their value to the work we create. Aside from that, I enjoy the ability to conceptualize snippets from my personal experiences and shoot them in more controlled environments. It’s always a unique involvement and no matter how long I’ve been doing this work I leave each set with a new takeaway to improve the next project.

In addition to being a photographer, you occasionally teach Ironworking through the San Diego Building Trades and community colleges. How did this happen? Why is this important to you?

In 2015 I joined the Ironworkers Local 229, out of San Diego. I successfully completed my apprenticeship and became a JIW, emphasizing in structural and ornamental welding. In 2023, after completing my OSHA 500 certifications I became eligible to train and certify students in their OSHA 30.

When I joined Local 229 in 2015 there were 8 active women in the trade and none of them looked like me or shared my path. It was very intimidating work initially, but I also found myself with limited opportunities, so I kept my head down and followed through with the path of becoming an Ironworker. Little did I know Local 229 would be some of the most informative, knowledgeable and character-building years of my life. I spent my entire 20s building San Diego in a largely male-dominated workforce. I was fortunate enough to fall into crews and companies that really valued and respected my workflow and imparted their knowledge onto me. I also had the luck of meeting my best friend and fellow Ironworker sister, Jenifer Arce. Together she and I managed to navigate the trade and seek out higher opportunities.

When the pandemic struck in 2020, Jenifer and I were considered essential workers and would spend our days off at food drives, passing out hundreds of boxes over the course of several months. Through that work we connected with Carol Kim, the San Diego Building Trades Business Manager. Through the door of community involvement and now friendship of Carol Kim, an opportunity arose through workforce partnership grants, and because of our knowledge, certifications, and good standing within the union we were able to interview and be selected to teach the MC3, which is a multi-core curriculum and an apprenticeship readiness program.

I was able to step away from the field of Ironwork and move into a classroom setting, educating students on the various union trades that exist, giving underserved communities the opportunity of lifelong careers in a field with fair labor practices, great benefits and livable wages. Doing this line of work has proven to be very rewarding and a way for me to contribute back to my Local 229. Although I no longer teach full time through the San Diego Community Colleges, I still teach seasonally, just having wrapped up an all-girls summer youth class at the University of Iron, where I was able to educate and give hands-on tutorials in welding, torch cutting, construction safety, and several other aspects of the trades including electrical and sheet metal.

Ten years ago, had you told me I would have been so accomplished as a female in my trade I would not believe you, but having wonderful union representation and leadership that supports the future of women in the trades has proven to be an invaluable resource to myself and the growing number of women who now see that there is a place for them in the construction industry.

If you could photograph another subculture anywhere in the world, what would you photograph and why?

I have a handful of answers to which I could respond, but narrowing down the options I would choose to photograph something close to home. I’ve always been fascinated by the vendors and entertainers of la línea, the line crossing back from Tijuana into San Diego. In 2014 I did a small story that aired on KPBS through a borderlands class I took. In it, I walked the lines and spoke with various child entertainers who would juggle, perform acrobatic stunts, and even panhandle car to car. It was then that I had a small glimpse into a fascinating world.

Unfortunately, after having filmed and aired the project I shifted gears and never revisited the story. It’s a goal of mine to return to the line, but this time to document all performers of the line: from the Michael Jackson impersonators, fire breathers, to the person who sells statues of Jesus and other saints. Many of these people have stories to share and I find it to be a very interesting line of work, that probably has a lot of layers and connections to organizations beyond what the surface shows. There is a world of politics and rules to decode. I find it fascinating and see it as a tangible project that I will undertake within this next year.

If you could tell 10-year-old Chata anything, what would you say?

I would tell her to worry less and enjoy the present because everything is temporary. Also, it’s okay to say no, only say yes if your heart is in it.

What's next for you?

In the short term, I have an upcoming show/exhibit opening September 5th, 2025, called TEÓ. It’s a group show curated by Patricio Chavez and Fedella Lizeth hosted at the Centro Cultural de la Raza in Balboa Park. I’ve spent this last summer producing new work that I am very excited to share. In the long term, I have some projects that are in process of completion, all of which include archival work that platforms Mexico, San Diego, and familial ties. Additionally, my end goal is to start learning the craft of cinema and storytelling through the process of video documentation. Just in the way I’ve always loved photography, I also feel called to motion picture. For now it’s not lack of resources but more so time and dedication, which I am constantly navigating.